Archeology of Myth : Sparta

Sparta

Sparta was one of the most prominent city-states in ancient Greece. Along with another best known city-state in Greece Athens, Sparta dominated the political landscape of Greece for a long time. Sparta is situated in the fertile Eurotas valley of Laconia to the southeast of Peloponnese. Archeological evidence points out that the area was first settled during the Neolithic period and developed as an important human settlement during the Bronze Age. Evidence regarding the bronze habitation of the region was found by the archeologists. But it was only in the early Iron Age that the four villages of Pitana, Mesoa, Limnae, and Cynosoura located near the Spartan acropolis came together to form the great city of Sparta. Proximity of the early city to the fertile valley of Eurotas made lot of nutritious food available to its inhabitants. According to Greek mythology, the city-state of Sparta gets its name from the daughter of King Eurotas called Sparta. King Euratos got Sparta married with Lacedaemon, the son of god Zeus. Lacedaemon named his kingdom with his own name and its capital with the name of his wife Sparta. Located on the banks of Eurotas Rives in the Pelopennesian Peninsula, the city emerged as a political entity in the 10th century BC when it was invaded and occupied by Dorians. Under the durians, it rose to become a leading military power in ancient Greece. After the Peleponnesian war (431-404 BC), Sparta emerged as the undisputed military and political power in the Greek mainland, Ionia, and Asia Minor. During its heyday, Sparta was the main enemy of another city-state Athens and defeated the latter in the Peleponnesian war. However, the defeat of Sparta by another Greece city state Thebes in 371 BC had put an end to its dominant role in Greece politics. Finally, Sparta lost its political independence after it was conquered by the Roman Empire in 146 BC.

An interesting aspect about Greek history was that, different gods and goddesses have assumed a vital role in different areas of the Mediterranean. Of particular importance are the goddesses of Athena and Artemis who received significant attention from the citizens of Sparta in the form of temple dedications, festivals, and sacrifices. Archeological findings from Sparta gave corroborating claims about Spartan origins. New excavations gave credence to the old belief that Sparta was inhabited by an earlier race other than the Dorians like Eretrians and Euboins. In Strabo’s Geography written in the 1st century CE, he said that Sparta was once inhabited by races like Eretrians and Khalkidians who had later abandoned the place due to a variety of factors like natural disasters and internal dissent between themselves.

This sample is posted to serve as an example to the quality of papers written by our professional essay writers. Please contact our support department to know more about the academic writing help offered by Academic Mentor Online.

Sparta and Mythology

There are several references in Greek mythology regarding the city-state of Sparta:

Histories by Herodotus

The classical historical epic of Histories by Herodotus has references regarding the bravery of Greek warriors (Histories, book 7, chapters 133-137). During the reign of the Persian king Darius, ambassadors were sent to Sparta demanding obedience by submitting water and earth as a symbolic tribute. Spartans threw the ambassadors into a pit which is generally used to punish hardcore criminals. After the incident, Spartans became distressed at their rude behavior and sent two Spartan warriors Sperthias and Bulis to offer themselves for execution. The new Persian king, Xerxes didn’t execute the warriors but took them on a tour of his army and navy to show the futility of a war with the great Persian Empire.

Another example regarding the idealism was also mentioned in Herodotus’ (Histories, book 3, chapter 46) where an emissary from the island of Samos was asked to simplify his request for help to overthrow their ruler Polykrates. Though rejecting an initial detail plea, Sparta extended its help when the emissary put up a simplified request by showing and empty grain sack.

Sparta in Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey

The history of Sparta and its heroic warrior was mentioned in the mythological poems Iliad and Odyssey. In the Trojan War that was fought between the Greeks and the Trojans, Sparta was an important member of the Greek force. Indeed it was the king of Sparta, Menelaos who had instigated the war after his wife Helen was abducted by prince Paris of Troy, Paris. Helen was offered to Paris by the goddess Aphrodite as a trophy for choosing her in a beauty contest over her fellow goddesses Athena and Hera.

Xenophon’s Anabasis

Xenophon’s Anabasis (book 7, chapter 1) has an interesting story regarding the dominance of the city-state of Sparta in Greece and the absolute control that Spartans had on their country. The story revolves around six thousand battle hardened mercenaries who were returning from a battle. On their return journey, they were confronted by a few red-cloaked Spartan military officers when they decided to stay in Sparta for a while to take rest. The mercenaries have quietly left Sparta even though they would have confronted the Spartan military officers as they knew that such an act would never be forgiven by Spartans. This story shows that Spartans’ authority over their city was never questioned by anybody.

Prominent Archeological Sites in Sparta

Archeological excavations at Sparta started with the setting up of the British School at Athens (BSA). BSA was founded in the year 1886 with the objective of promoting classical studies and archeology. Excavations conducted by the archeologists associated with BSA and the American School of Classical Studies during the late 19th century and early 20th century revealed a lot of ancient treasures in Sparta (Meader 1893). Excavations by BSA were chiefly concentrated in two different periods of the 20 the century. During the first period, excavations were chiefly undertaken within the city of Sparta and nearby surroundings like City Walls, Heroon, Great Altar near Eurotas, shrine of Athena Chalkioikos, shrine of Menelaos and Helen. The second phase of field research which lasted from 1919 to 1929 under the leadership of the then BSA’s director A.M. Woodward and focused on the Roman Theatre on the southern slope of the Spartan Acropolis hill. After the end of the second phase, other than two important rescue operations undertaken by two BSA’s archeologists J.M. Cook and R.V. Nicholls in 1949, no major work was attempted by BSA in Sparta for more than forty years. The excavations at Sparta have later progressed over the period and continued till the start of the 21st century.

Below are some of the prominent archeological sites in Sparta:

Temple of Artemis Orthia

Temple of Artemis Orthia, one of the famous archeological site found in Sparta, was built around 6th century B.C. It was built for Artemis, one of the most widely venerated of the Ancient Greek deities. The Temple of Artemis Orthia was the hub of Orthia cult which was widely practiced in the ancient four of villages which formed the state of Sparta: Limnai, Pitana, Kynosoura, and Mesoa. The temple was located in the natural basin between Limnai and Eurotas. It was located outside the town of Sparta and young men who were trained to be warriors underwent through initiations (krypteia). Krypteia involved severe public floggings till the altar of the temple was splashed with blood to satisfy the goddess. Archeological finds of the place have traces of two such altars in the temple complex. A major part of the remaining ruins of the temple were the ones built by the Romans in the 3rd century B.C. who have revived the tradition of public flogging. Ancient relics like pottery fragments found during the archeological excavations indicate that the cult of Orthia has been in practice since the 10th century before.

Temple of Athena Chalkioikos

The temple of Athena Chalkioikos was designed by the architect Vathyklis from Magnesia. It is located to the top of the Spartan Acropolis and the north side of the theater. Interiors of the temple were adorned with copper sheets (from 6th B.C.) from which the temple derives its name (Copper = Chalkioikos). The Temple of Athena Chalkiikos had a bronze statuette of Athena, statue of Leonidas, statuette of a trumpeter, and a cult statue created and erected by a local man called Gitiadas. Some evidences regarding the Spartan power still remain from the excavations near the temple of Athena Chalkioikos. The spectacular ancient theater of Sparta which was a product of the early imperial period was one such evidence of the influence wielded by Sparta. Adjacent merchant stalls to the auditorium discovered in excavations by the British School during the early 1990s served the audiences during performances held at the theatre.

Mount Ithome

Mount Ithome is an important site located at some distance to Sparta but contributed a lot for the understanding of the ancient Sparta. During the Bronze Age, a temple of the Greek god Zeus Ithome was located there. However, the temple was later demolished in the 14th century and a Christian church was built using the same stones. According to the findings of the excavations, the cult of Zeus in the Ida cave begins in 8th century B.C. as it does at Messene. According to Greek archeologists Sypros Marinatos and Paul Faure the legend of Zeus child was introduced by Peloponnesian colonists (Marinatos 1962).

Apothetes

The first century Greek historian, Plutarch in his narrative on the lives of nobles has mentioned of a site called Apothetes where Spartans would kill unhealthy babies by throwing them from a mountain top into a pit called Apothetes. According to the myth, Spartans used to submit their new born infants to the elder members for getting them physically inspected regarding their fitness. If the newborns were found to be too tiny, ill or deformed; elders of Sparta would throw them into the Apothetes pit which is situated at the base of Mount Taygetos. Mount Taygetos has been continuously inhabited since the Mycenean times and was one of Sparta’s natural defenses against the invading forces and natural disasters. There was no other record of this infanticide in any mythological sources. However, recent research by archeologists of the University of Athens and Cambridge University didn’t find any evidence regarding the killing of babies. Excavations in the area revealed that the bones found in the pit were those of the adolescents and adults between the ages 18 and 35. Archeologist Theodoros Pitsios of Athens Faculty of Medicine (University of Athens) debunked the reports in Greek mythology regarding Apothetes being a site for infanticide. According to the remains excavated from the site, the bones found in the pit were not that of infants and added that it was just a myth. Pitsios added, “There were still bones in the area, but none from newborns, according to the samples we took from the bottom of the pit.” Archeological findings had shed light on the second war between Sparta and Messene, an independent strong state in olden Greece. Pitsios said that when Messene was defeated by Sparta, Messenian warrior Aristomenes and his band of 50 warriors were all killed and thrown into the Apothetes pit. Research on the findings proved that the bones belonged to 46 men and came from the fifth and sixth century BCE. Archeological evidence proved that Apothetes was primarily a place for the execution of criminals, captives, and traitors.

Menlaoin

Menlaoin was an important Mycenaean site which is located at some distance from Sparta. During the excavations conducted by BSA, one of the first sites to attract the attention of archeologists in the surroundings of Sparta was a huge monument built in a striking position on a plateau above the bank of Eurotas which was located three kilometers from the centre of the modern Sparta. In 1833, archeologist Ludwig Ross proposed that this building must have been the Shrine of Menelaos and Helen who were first referenced in Homer’s epics. Shrine of Menelaos and Helen also had other frequent references in Greek mythology like in the tale of ugly baby girl in Histories by Herodotus (Catling 1977). After forty years, the site was visited by German businessman-archeologist Heinrich Schliemann who has recovered a postsherd from 6th century with “I belong to the hero” inscribed on it. This finding rekindled archeological interest in heroic cult practiced in ancient Greece. Peasants who were working in their fields around Menelaoin continued to find relics like votive offerings made to gods belonging to metal and clay. Concentrated excavations made by BSA in 1909 established for the first time that the age of the shrine of Menelaos and Helen was very old and the shrine had been in existence from the Late Geometric times until the Hellenistic period. An important finding at the Menelaion was the rectangular base which seated the god (hero) of the temple Menelaus, the King of Sparta. Subsequently, archeologists gave the age of fifth century for the monument. The 1909 excavations shed further light on the Bronze Age occupation of the site after rich deposits of terracotta, bronze, and lead objects were unearthed. Two theories of heroic cult have gathered support in the course of research on the findings from the site. The first of the two theories was that heroic cult was a continuance of native indigenous cult prevalent from aboriginal days. A second theory holds that the spread of Homeric epics inspired Greeks to adopt heroic cult of affirming their association with Mycenaeans and the Heroic era of ancient Greece.

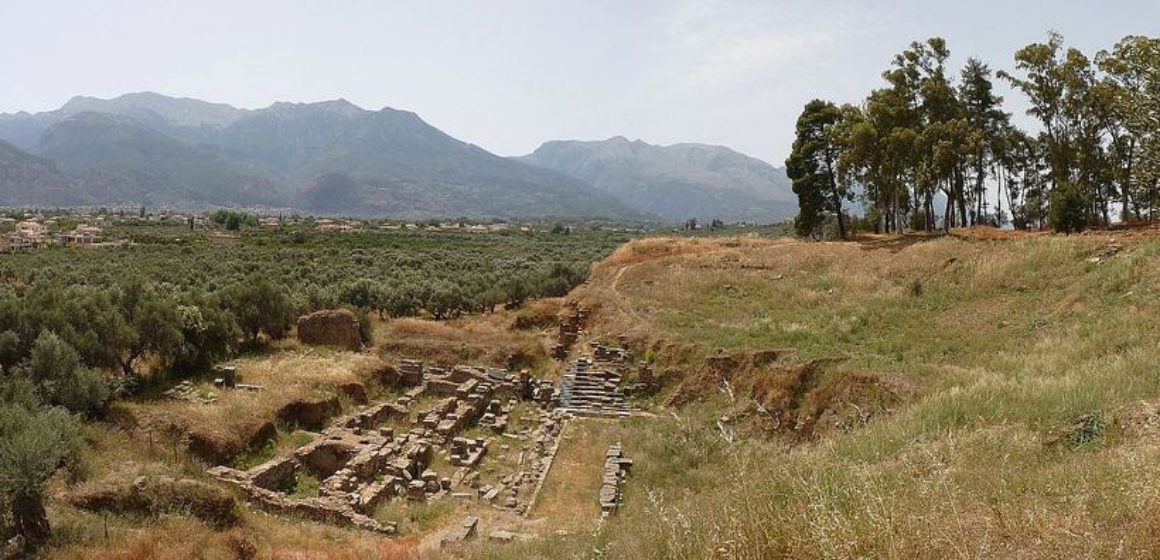

Theatre of Sparta

Ancient theatre at Sparta is another important archeological find at the south of the acropolis. Theatre of Sparta belongs to the early imperial period and was built huge to seat 40,000 spectators. Theatre of Sparta is considered to be one of the biggest of the ancient theatres in Greece and looks striking to eyes even in these days. Remains of the theatre of Sparta still preserve the orchestra, some cavea where animals were confined before the games, and walls with inscriptions by the roman rulers who have later occupied the city state. During the old and latest excavations by BSA, at the theatre of Sparta, shops which catered to the needs of theatre’s spectators who attended performance and other kind of shows were discovered (Catling 1995). Shops surrounding the theatre of Sparta were constructed during the Roman imperial period with burned bricks and their interiors were decorated with plaster. In sync with the mythological accounts of the performances held at the theatres, excavations conducted during the early 1990s by BSA gave new evidence regarding the stage arrangements made during the construction work made by G. Julius Eurykles, c. 30-20 B.C. (Waywell and Wilkes 1999).

Conclusion

Sparta, like Athens, was one of those sites of Greece which has many mythological parallels. Archeological findings at Sparta have shed light on mythological tales and gave evidence to Homer’s tales and the historical accounts mentioned in Herodotus’ Histories. But despite the many attempts made by archeologists, there is still no concrete evidence linking the places of the archeological findings in Sparta with those of the references from the mythology. But being on the important hubs of Greek civilization, academicians and journalists will continue with their quest in exploring their relationships between Spartan findings and the references made in Greek mythology. The latest archeological findings like those from the theatre of Sparta mentioned above promise more facts to be revealed in future excavations. More excavations can shed light on the happenings mentioned in mythological tales.

References

- Catling, H.W. 1977. “Excavations at the Menelaion Sparta, 1973-1976”, Archaeological Reports, vol. 23, pp. 24-42.

- Catling, H.W. 1995. “The Work of the British School at Athens at Sparta and in Laconia”, British School at Athens Studies, vol. 4, pp. 19-27.

- Herodotus, 2003, Histories, Penguin, London.

- Homer, 1887, Iliad, Ginn & Company, Oxford.

- Marinatos, S. 1962. “Die Wanderung des Zeus”, Foncflonsdes, AA, pp. 907-916.

- Meader, C.L. 1893. “Reports on Excavations at Sparta in 1893”, The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History in Fine Arts, vol. 8, pp. 410-428.

- Plutarch, 1977, Parallel Lives, Modern Library, New York.

- Spartans didn’t throw deformed babies away: researchers, Available from: http://www.genuine-orthodox.net . [13 December 2007].

- Waywell, G.B. and Wilkes, J.J. 1999. “Excavations at the Ancient Theatre of Sparta 1995-1998: Preliminary Report”, vol. 94, pp. 437-455.

- Xenophon, 1852, Anabasis, Harper & Brothers, New York.